Bishop Brian Noble

Lenten Talk on the Eucharist

To begin, then, let me remind you of a variety of words associated with our theme - Eucharist; Mass; Holy Communion; Real Presence; Blessed Sacrament; Exposition; Benediction - and now let me invite you to think of an event to which all of those words relate - an event in which all of them have their origin… That event, let me suggest, is the Last Supper - Jesus' final meal with his disciples.

So whether we're at Mass, or quietly praying alone before the Blessed Sacrament; whether we're taking Communion to the housebound or receiving Communion in hospital; attending Benediction or walking in a Blessed Sacrament Procession - no matter what the activity - I suggest that our starting point for understanding what we're about, must always be found in the Last Supper.

"When the hour came, he took his place at table... Then he took a loaf of bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and gave it to them, saying 'This is my body, which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me.' And he did the same with the cup after supper, saying, 'This cup that is poured out for you is the new covenant in my blood." (Luke 22: 14, 19f)

It's here that we must always begin, and for deepening our understanding it's to this, the Last Supper, that we must continually return. And this evening I want to do so by exploring that event in terms of change and transformation. It's not surprising, I suppose, that when we begin to think of the Last Supper in this way, we inevitably home in on the change implied in the words: "This is my body... (This is) my blood" - in other words, the change, the transformation that traditionally we call 'Transubstantiation' - the changing of the bread and wine into the Body and Blood of the Lord. But in addition to that change, there are other changes that are equally important for our understanding, and the significant words here are not just "This is my body... This is my blood" but "This is my body... given for you... (This is my blood) poured out for you": There's a wealth of meaning here which we mustn't miss. And first of all we might notice what Jesus is saying about his relationship with the apostles; he's not just one among equals or a friend among friends, or even a leader among his followers. Rather He is to them pure Gift - given to them and for them. And it's his words accompanying his invitation to drink, that express the totality of this giving: "(This is my blood) poured out for you': Already then, here at the Last Supper, the inevitable events of Good Friday are being anticipated and Jesus is making it clear that He sees his death as the ultimate sign of being totally given on their behalf. "No one has greater love than this": wrote St John, "to lay down one's life for one;s friends" (John 15:13). All of which brings us back to change and transformation. In the Cross of Jesus, the hatred and violence involved in his being put to death is met, not with further violence and more hatred, but with acceptance and forgiveness; and his Cross, initially a sign of evil, is transformed into a symbol of love.

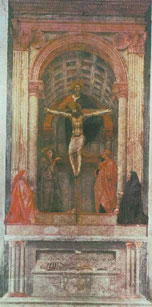

In one of the churches in Florence, there's a famous fresco by the artist Masaccio - which you have reproduced on the card. It's a painting of the Trinity - though at first sight you might be forgiven for thinking it to be simply the Crucifixion. But look again and there, above and behind the crucified Christ, is God the Father - arms outstretched and supporting the Cross, but also outstretched in a gesture of giving the crucified Christ to us. The artist is taking us to the very heart of what the Cross is all about, and he's locating it where it truly belongs - namely within the Mystery of the Trinity: Jesus is the Father's Gift to us; and his Cross, the Father's instrument of evil's defeat, the proclamation of forgiveness, and the sign for all time of Love's triumph. And the validation that all of this is so, was made clear on the Third Day, when, as the Letter to the Philippians makes clear, having "humbled himself... to the point of death... death on a cross... God highly exalted him" ... to become, as the Letter to the Colossians put it "the first born from the dead"(PhiI2:8f; Col 1:18).

In one of the churches in Florence, there's a famous fresco by the artist Masaccio - which you have reproduced on the card. It's a painting of the Trinity - though at first sight you might be forgiven for thinking it to be simply the Crucifixion. But look again and there, above and behind the crucified Christ, is God the Father - arms outstretched and supporting the Cross, but also outstretched in a gesture of giving the crucified Christ to us. The artist is taking us to the very heart of what the Cross is all about, and he's locating it where it truly belongs - namely within the Mystery of the Trinity: Jesus is the Father's Gift to us; and his Cross, the Father's instrument of evil's defeat, the proclamation of forgiveness, and the sign for all time of Love's triumph. And the validation that all of this is so, was made clear on the Third Day, when, as the Letter to the Philippians makes clear, having "humbled himself... to the point of death... death on a cross... God highly exalted him" ... to become, as the Letter to the Colossians put it "the first born from the dead"(PhiI2:8f; Col 1:18).

Well, perhaps it may seem that we've wandered far from the Last Supper and it's continuation in the Eucharist, but that isn't so. And the Liturgy is there to prove it. In response to the Words of Institution "This is my body... This is my blood" notice how we respond: Not, as you might expect, "O Sacrament most holy, O Sacrament divine": but rather "Dying you destroyed our death; rising, you restored our life'; "By your cross and resurrection you have set us free, you are the Saviour of the world". As with the Last Supper, every celebration of the Eucharist is always and essentially a celebration of the death and resurrection of the Lord, and as such, every Eucharist is a celebration of the change, the transformation, that has occurred in humankind's relationship with God... "You are the Saviour of the world".

But that is not all, and to take us further - another painting. Again it's a painting of the Trinity - the now famous icon by the 15th century Russian, Rublev. Many of you will know it. The Biblical background to the story is in the Book of Genesis. It's the story of the three mysterious visitors who arrived at Abraham's tent with news that his wife Sarah would have a child. Christian Tradition has long seen these visitors in terms of the three Persons of the Trinity, and Rublev follows that Tradition in using the story for his portrayal of Father, Son and Holy Spirit. But for our present purposes, the interest of the icon lies in his depiction of the food Abraham prepared for his visitors - as painted, it is clearly the Bread of the Eucharist, and in linking Trinity and Eucharist, Rublev is making a statement every bit as profound as Masaccio's linking the Trinity and Calvary. Just as "the Cross has its origin in the heart of the Trinity, so, it's in the Trinity that the Eucharist has its goal.

But that is not all, and to take us further - another painting. Again it's a painting of the Trinity - the now famous icon by the 15th century Russian, Rublev. Many of you will know it. The Biblical background to the story is in the Book of Genesis. It's the story of the three mysterious visitors who arrived at Abraham's tent with news that his wife Sarah would have a child. Christian Tradition has long seen these visitors in terms of the three Persons of the Trinity, and Rublev follows that Tradition in using the story for his portrayal of Father, Son and Holy Spirit. But for our present purposes, the interest of the icon lies in his depiction of the food Abraham prepared for his visitors - as painted, it is clearly the Bread of the Eucharist, and in linking Trinity and Eucharist, Rublev is making a statement every bit as profound as Masaccio's linking the Trinity and Calvary. Just as "the Cross has its origin in the heart of the Trinity, so, it's in the Trinity that the Eucharist has its goal.

The bread that is his Body "given" for us, the wine that is his Blood "poured out" for us - these are given so that, with Him, we can be where we truly belong - namely, with the Father, in union with the Son through the Spirit. And if this sounds rather unfamiliar, let me reassure you with words that are very familiar:

"Father ... look with favour on your Church's offering, and see the victim whose death has reconciled us to yourself. Grant that we, who are nourished by his body and blood, may be filled with his Holy Spirit and become one body, one spirit in Christ. And may he make us an everlasting gift to you and enable us to share in the inheritance of your saints" (EP 3).

Those words of the Third Eucharistic Prayer make it clear enough that the Eucharist is so much more than a private matter between the Lord and myself; so much more even than a celebration of his presence by a group of disciples. He is "given": not that He may become me, but that we may find in Him a new identity - changed, transformed, to "become one body, one spirit in Christ": and thereby be drawn into the love that is the life of the Trinity. Rublev's icon speaks simply, yet profoundly, of this truth.

And to discover the consequences, let me remind you again of the story of the disciples on the road to Emmaus. You'll remember that it was in the Breaking of Bread that their eyes were finally opened and they fully recognised the Risen Christ. And having done so, notice the change, the transformation. They take on a new lease of life - divine life, dare we not call it? - and, with alacrity, they retrace their steps, and return to Jerusalem. That often overlooked detail of their return to Jerusalem is so much more than a 'lived happily ever after' conclusion. It's the statement of what life that comes from the Eucharist involves. They return to Jerusalem to be reunited with the other disciples in their awareness of what the now Risen Lord had achieved for them in his life and death - "Were not our hearts burning within us while he was talking to us on the road?" (Luke 24:32). That return journey, after the Breaking of Bread, to be with the other disciples in Jerusalem, is a permanent reminder of the source of our belonging to each other. It's a unity that has nothing to do with age or nationality, nor with common interests or ideology. It arises entirely from our becoming "one body, one spirit" in Him. As Paul put it in writing to the Corinthians: "The bread that we break, is it not a sharing in the body of Christ? Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread" (I Cor 10: 16f) And so at Communion in answering "Amen" to the words "The Body of Christ': we're not only professing our faith in who it is we are receiving, we're equally expressing our faith in who it is we are more fully becoming. And as we hear the words: "Go the Mass is ended" and make our way back to the Jerusalem of our everyday lives, it's together as his living presence that we go. And bringing us back to where we began, it's in the sign of the bread that is broken and the cup outpoured, that the cost of such discipleship is made clear. "a disciple" the Lord told us, "is not above the teacher, nor a servant above the master" (Matt 10:24). Commitment to his Kingdom and his values will inevitably replicate in us his way - the way of the Cross - but that, as we also know, is the way to life.

Well, it may seem we have come a long way from where we began. But in fact we've done nothing more than to tease out a little the significance of that momentous Supper the night before Jesus died, and I repeat, that the Eucharist - whether celebrated, received or adored - cannot and must not be understood apart from that Supper and all that was to follow. "The Lord Jesus on the night he was betrayed" (I Cor 11 :23) writes the Holy Father in his most recent encyclical letter on the Eucharist "instituted the Eucharistic sacrifice of his body and blood" ... This, he says, is "the dramatic setting in which the Eucharist was born". And he goes on to emphasise that, "The Eucharist is indelibly marked by the event of the Lord's passion and death of which it is not only a reminder but the sacramental re-presentation. It is the sacrifice of the Cross perpetuated down the ages" (Ecclesia de Eucharistia 11).

It's the Church's desire to make sure that we don't lose sight of this rich belief that has given rise over the years to a number of modifications in the way we do things connected with the Eucharist. And it might be helpful to mention a few. Those of us who are geriatric - to a modest or advanced degree - will remember old style Benediction and Quarantore, marked by a lofty throne for the Blessed Sacrament and serried banks of flowers and candles. Several decades ago, Rome issued new guidelines - requiring much greater simplicity and - significantly - the Blessed Sacrament to be, not on a throne but on the altar. Why? Because we must never separate the Eucharistic Presence and the Cult of the Blessed Sacrament from the Altar of Sacrifice. The Lord who is present and adored is the crucified and risen Lord.

And paradoxically perhaps, for the same reasons, guidance was given that the permanent Reservation of the Sacrament should always be fittingly housed, but not on the altar itself. Why? Lest the Table of Sacrifice be considered little more than a pedestal for the Tabernacle. What is done at the altar must never be thought less significant than the tabernacle and its contents.

And it's for similar reasons that the custom of receiving Communion under both kinds has been re-introduced. The cup and its contents - "poured out" for us - reinforces our understanding that it is the risen, yet crucified Christ that we receive: "The cup of blessing that we bless, is it not a sharing in the blood of Christ?" (I Cor 10:16) wrote St Paul; and to take the chalice and drink, can be a powerful reminder to us of the cost of our discipleship. Remember Jesus' words to James and John after their request to have places on his right and left: "You do not know what you are asking. Are you able to drink the cup that I drink?" (Mk 10:38)

And so, to round off. What I've been attempting to do, is to ensure that in all our involvement with the Eucharist - in celebrating Mass, receiving Communion, praying before the Blessed Sacrament - that in all of this, we appreciate the full truth of what we are about. And, in the light of this truth, by way of conclusion and preparation for Part 2 of our evening, let me suggest three ingredients for what we might call Eucharistic Devotion. The first is simply reflection - a prayerful calling to mind of our Eucharistic Faith - maybe going back in our imaginations to the Last Supper and the events that followed; or to the experience of the Emmaus disciples. Or perhaps taking one or other of the Eucharistic Prayers and considering its content prayerfully - all of which can be gateways to deeper appreciation. And that will surely bring us to a second ingredient - namely, gratitude and a prayer of thankfulness. Gratitude for all that the Lord has done; gratitude for the change and transformation He's achieved on our behalf; gratitude for all He's given. And finally, from thankfulness to a prayer of commitment - to his Way, his Truth and Himself as our Life. "When we eat this bread and drink this cup we proclaim your death, Lord Jesus, until you come in glory" -"Come, Lord Jesus" (Rev 22:20).

+ Brian Noble

Bishop of Shrewsbury

- This talk was given as part of the Diocese of Shrewsbury's Year of the Eucharist (2003—4) during Lent 2004 in:

- 2 March 2004 — St Nicholas Catholic High School, Hartford

- 9 March 2004 — All Saints Catholic College, Dukinfield

- 10 March 2004 — Blessed Robert Johnson Catholic College, Telford

- 16 March 2004 — Plessington Catholic High School Technology College, Birkenhead

- 25 March 2004 — St James' Catholic High School, Cheadle Hulme